Revival of Maghamaka Mahotsava

Kerala, nestled between the majestic Western Ghats and the vast Arabian Sea, has a history steeped in culture and tradition. The region now known as Malappuram district was once a thriving center of Vedic learning and religious practices. This sacred land, home to many deities and their temples, witnessed grand festivals celebrating divine traditions—some of which were lost over time due to historical upheavals.

Among these ancient celebrations, Maghamaka Mahotsava stands out as Kerala’s oldest river festival, held on the banks of the sacred Bharatapuzha River during the auspicious month of Makam. Rooted in Kerala’s deep Vedic heritage, this festival was traditionally conducted under the patronage of Kerala’s ruling kings. However, its observance came to an abrupt halt in 1766 AD following the invasions of Hyder Ali and later Tipu Sultan.

In 2019, in an earnest endeavor to revive this lost legacy, the Oral History Research Foundation and UgraNarasimha Charitable Trust rekindled the festival. This historic revival continues with the Maghamaka Mahotsava 2020, set to take place on the sacred banks of Bharatapuzha in the villages of Thirunavaya and Thavanur, Malappuram.

Maghamaka Mahotsava 2020

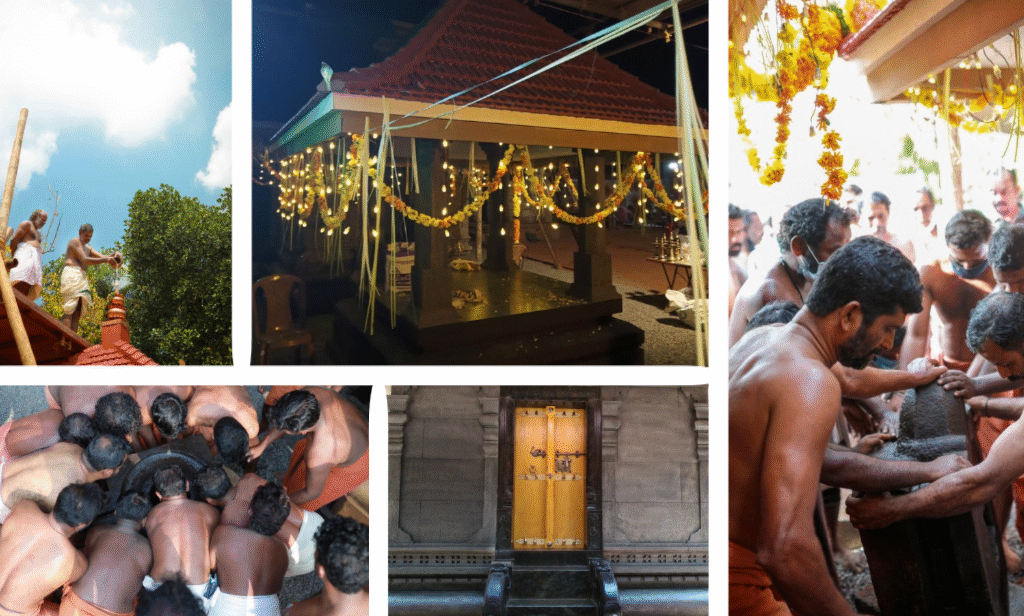

From January 10 to 12, 2020, under the spiritual guidance of the revered Devi Upasaka, Tantric Acharya, and Srividya Sadhaka, Shri Ramesh Nataraj Iyer (GRD Iyers Gurucool, Canada), over 100 ritwiks from Canada, the USA, Singapore, and various states across India gathered to perform the Dwi Shata Chandi Yagam and Maha Rudra Homam at Tavanoor—the Trimurti Sangam, where Parashurama is believed to have undertaken intense penance.

The spiritual celebrations culminated at sunrise on January 13, 2020, with a series of sacred rituals led by the esteemed Brahmashri Chidanandapuri. These included the Nila Puja, Nila Arati, Nila Snanam, Sanyasi Sangamam, and Yati Puja at the historic Navamukunda temple premises.

Shata Chandi Mahayajna

Conducted on January 10-11, 2020, this grand Yajna, performed as per the Sri Vidya tradition, took place in the very village where Sage Parashurama is said to have organized a similar sacred fire ritual eons ago.

Rudra Mahayajna

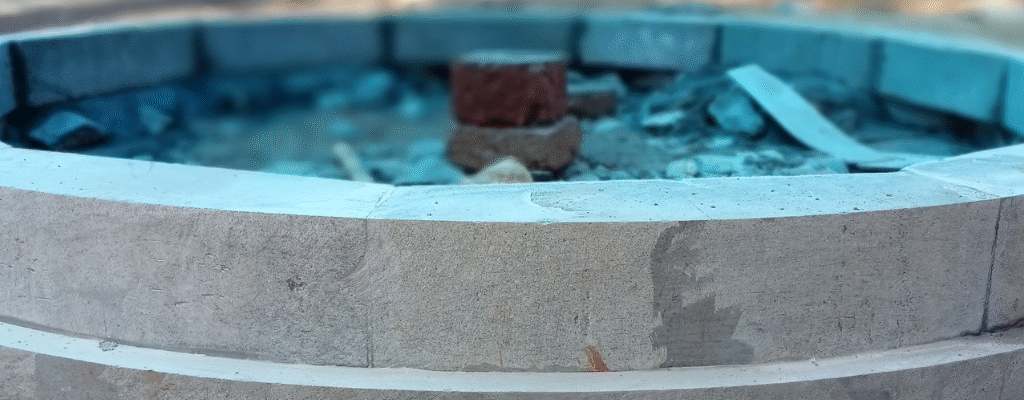

On January 12, 2020, the Rudra Mahayajna was conducted with great devotion. Devotees had the rare opportunity to perform the Abhisheka of a Shivling consecrated at the sacred Yagabhumi.

The Legacy of Maghamaka Mahotsava

The origins of Maghamaka Mahotsava are deeply embedded in Hindu scriptures. The Puranas and other Smritis attest to its conception by Parashurama. Literary works from the Sangha period, such as the Divyaprabandham, reaffirm this tradition. European historians like Hamilton and Jonathan Duncan, along with accounts from the Kozhikode Samoothiri Raja to the British throne in 1810, provide additional evidence of Bharatapuzha’s Maghamaka festivities.

According to legend, Parashurama, seeking prosperity and protection for Kerala, requested Brahma to conduct a grand yaga. The ritual was initially planned at Anamudi, Tamil Nadu. However, a dispute arose between Saraswati and Gayatri over the position of Yajamanapatni. Their subsequent curse upon each other resulted in their transformation into rivers that absorbed the sins of humanity, leading to the postponement of the Yaga. Eventually, the ceremony was conducted at Tapasannur (present-day Tavannur), a place sanctified by the penance of sages.

This grand Yajna, lasting 28 days, was attended by the Trimurtis—Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva—along with celestial beings and enlightened sages. The sanctity of the ritual led to the emergence of the holy Bharatapuzha River, enriched by the divine presence of Ganga, Gayatri, and Saraswati during the month of Magha. This spiritual significance led devotees from distant lands to flock to Nila River for a sacred dip, believing it would absolve them of sins accumulated over lifetimes.

The first Cheraman Perumal, anointed in Tirunavaya, oversaw the organized conduct of this grand festival. From that point, the right to host Mamankam—an evolution of Maghamaka Mahotsava—was established. Over centuries, the festival transitioned from an annual event to being held every three years, and eventually, every 12 years.

However, the tides of history turned violent. During one such Mamankam, the ruling Valluvakonathiri was assassinated by a faction led by Tirumanassery, paving the way for Kozhikode’s Samoothiri to claim control. This marked the beginning of bloodshed at the once-sacred festival. The history of Mamankam that survives today is largely from the era of Chekavars (warriors), while its ancient traditions remain obscure to modern generations.

The last recorded Maghamaka Utsava took place in 1766 AD. Following the invasions of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, the festival faded into oblivion.

The Vision of Maghamaka Mahotsava

The revival of Maghamaka Mahotsava aims not only to restore a lost tradition but also to rejuvenate the ancient Vedic villages of Thavanur and Thirunavaya. Thavanur, home to Kerala’s first Vedic Pathshala, now stands silent, devoid of its once-thriving scholarly pursuits. We believe that reviving this sacred river festival, along with its accompanying Yajnas, will restore prosperity to the region and bring spiritual enrichment to all participants.

Maghamaka Mahotsava 2020: A Glorious Revival

The Maha Rudra Yajna and Dwi Shata Chandi Yajna were successfully conducted with Shri Ramesh Natarajan and Smt. Gayatri Natarajan of GRD Iyer Gurucool as Acharyas. Over 100 Ritwiks from across Bharat and the world participated in this monumental Yajna from January 10-12, 2020.

During these sacred days, thousands of devotees gathered at the Yajnabhumi, witnessing and partaking in the divine rituals. The Abhisheka of the consecrated Shivling became a highlight, symbolizing the sanctity of the land and the power of devotion.

On January 13, 2020, a magnificent Nila Arati and Nila Puja were conducted on the banks of Bharatapuzha, led by revered Sanyasis and Sadhus. The sacred waters, believed to embody the presence of all holy rivers during this auspicious period, saw the ceremonial dip of sages who had assembled for the event. Swami Chidananda Puri of Advaitashram delivered an inspiring discourse to the gathered ascetics.

After being lost for over 250 years, the Maghamaka Mahotsava has finally returned. With the unwavering support of organizations and individuals, we hope to see it grow in grandeur, reclaiming its status as one of the most revered festivals of ancient Bharat.

May the sacred traditions of Maghamaka continue to flourish, restoring Dharma and prosperity to this blessed land.

Pledge now to start a recurring donation