Guide to offer Uma Maheshwara Puja

Uma Maheshwara Puja: Invite Harmony into Your Home

In a world that often feels rushed, scattered, and uncertain, there’s something deeply grounding about turning to age-old rituals that brought peace to our ancestors for centuries. Uma Maheshwara Puja is one such sacred practice—a heartfelt offering to Shiva and Parvati, the eternal couple who represent love, strength, and balance.

But this is more than a ritual.

It’s a quiet, powerful way to invite Shanti (peace) and Sampatti (well-being) into your home.

What Makes This Puja So Special?

Uma Maheshwara is not just a name—it’s a symbol of a complete life. When Shiva (the stillness, the protector) and Parvati (the nurturing force, the Shakti) are worshipped together, they bless your home with harmony, unity, and divine protection.

Whether you’re:

- Newly married and beginning a life together,

- A parent praying for peace in the family,

- Or simply someone seeking inner calm in a chaotic world…

This puja brings your intentions into a sacred space—guided by Vedic tradition, yet deeply personal.

The Puja Process – Rooted in Vedic Tradition

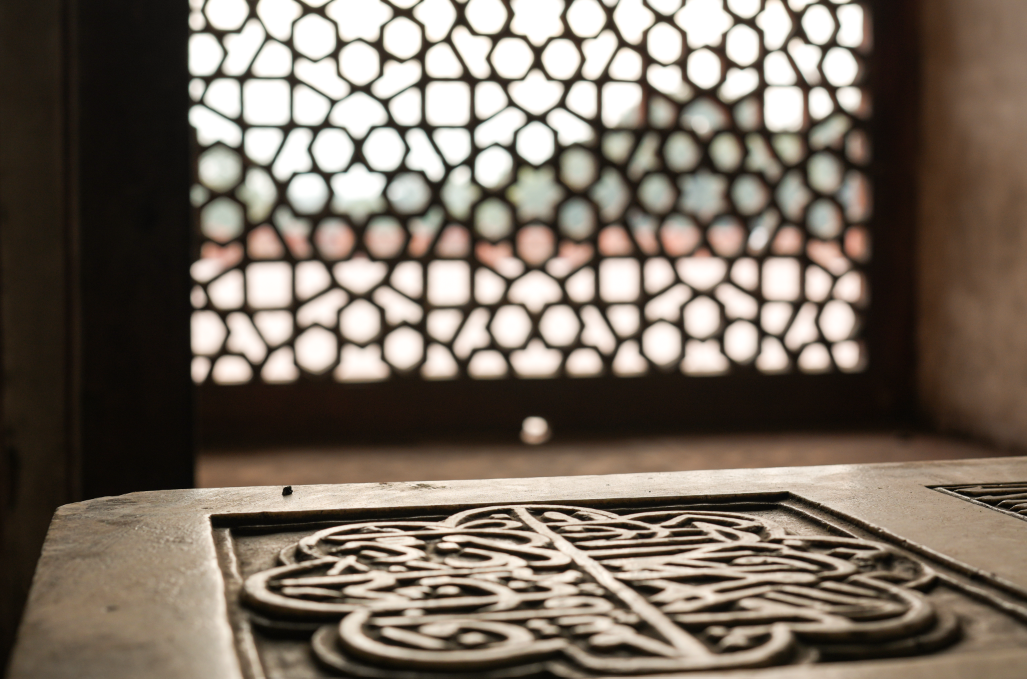

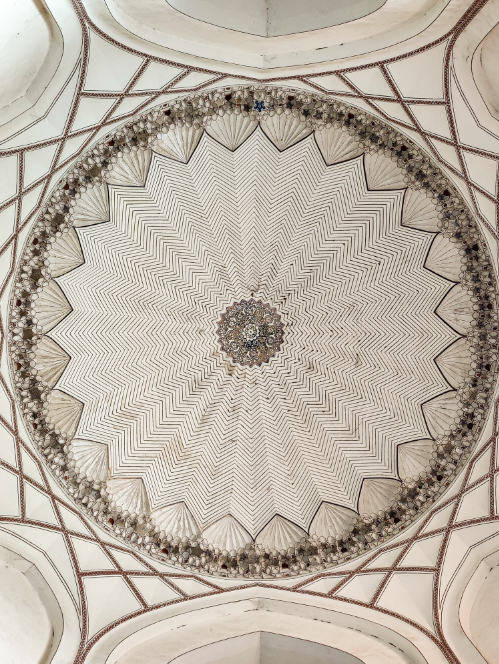

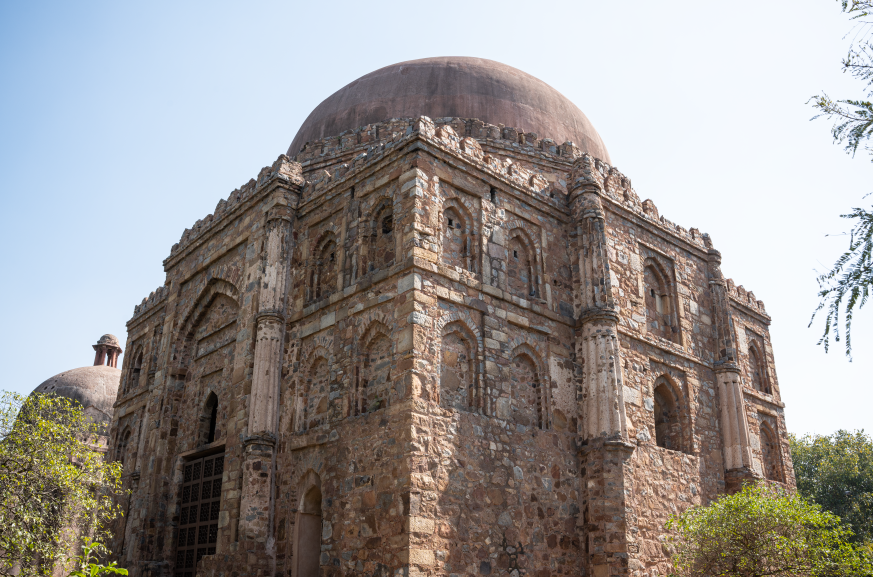

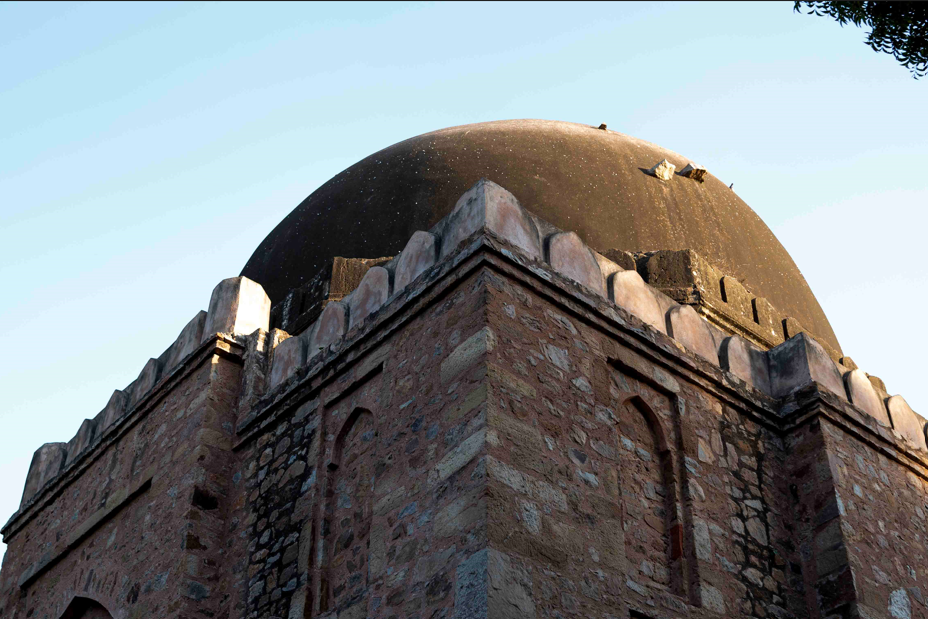

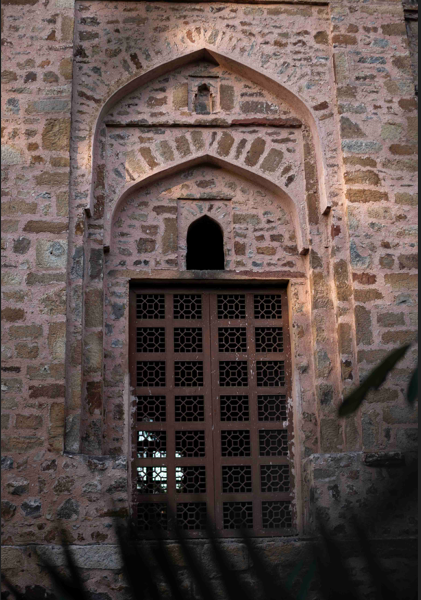

Your puja is performed by learned Vedic Pandits in a historic Shiva-Parvati temple restored through the Reclaim Temples movement.

Here’s how it works:

- You book the puja online, submitting your name, gotra, addresss to be delivered.

- On an auspicious day, our Vedic priests perform the complete Uma Maheshwara Puja:

- Abhisheka (ritual bathing of the deity)

- Pushparchana (flower offerings)

- Deepa aradhana (sacred lamp ceremony)

- Chanting of mantras and Vedic hymns

- Your name and sankalpa are recited during the puja, ensuring that your intentions are spiritually included.

- After the puja, prasadam (blessed offerings), kumkum, and vibhuti are carefully packed and shipped directly to your home, anywhere in India or abroad.

You don’t need to be present physically—the sanctity and blessings reach you wherever you are.

Why We Revived This Ritual

At Reclaim Temples, we don’t just restore temple stones—we restore living traditions.

This puja was once widely performed in ancient Bharat, especially in temples devoted to Uma Maheshwara. But as invasions and neglect took their toll, both the temples and the traditions faded.

Bringing this ritual back isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about healing—for families, for our culture, and for future generations.

When you sponsor or participate in a puja like this, you’re not only seeking blessings—you’re becoming part of a deeper, sacred reclamation

Let the Blessings Begin

Book a Uma Maheshwara Puja for:

- Marital harmony

- Fertility and family well-being

- Mental peace and emotional grounding

- Spiritual connection and divine grace

Each puja helps fund restoration efforts and revives forgotten temples—your devotion becomes a force of rebuilding.

📍 Conducted at a historic Shiva-Parvati temple, by learned priests

📩 Prasadam shipped to your home (India & abroad)

📿 Includes name/gotra sankalpa, archana, and blessings

Let this puja be your prayer, your offering—and your step towards reclaiming something timeless.

Because our ancestors left us more than ruins—they left us rituals that still work.

#ReclaimTemples