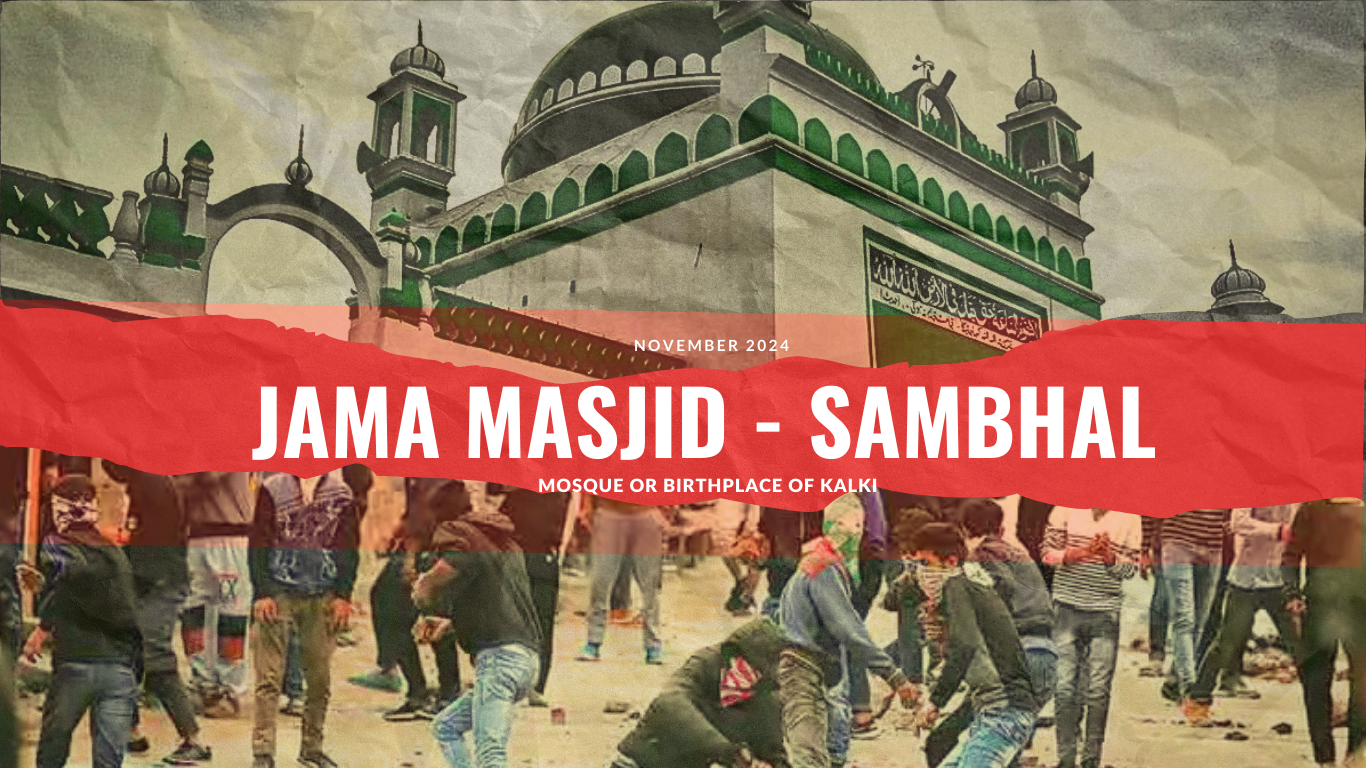

Jama Masjid Sambhal: A Case That Raises Questions Beyond Law

The Jama Masjid in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh, has been at the center of a legal and cultural debate after the Babri Masjid case.

It was hoped that the Ayodhya-Babri Masjid judgment, despite its legal flaws and shoddy reasoning, would put a closure to the mandir-masjid disputes once and for all. Perhaps this hope also led the Supreme Court to allow the Ram Mandir construction, despite finding that there was no conclusive evidence of any pre-existing temple beneath the Babri Masjid and declaring that the installation of idols inside the mosque in 1949 and the destruction of the mosque in 1992 were illegal. Probably, the Court intended this as a “one-time measure” because it categorically stated that historical wrongs by medieval rulers can’t be corrected by the present-day legal regime. More importantly, the 5-judge bench also upheld the Constitutional validity of the Places Of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991(PoW Act) as it was the fulfilment of the State’s “constitutional obligations to uphold the equality of all religions and secularism which is a part of the basic features of the Constitution. The Court observed that the PoW Act reflected the message that “history and its wrongs shall not be used as instruments to oppress the present and the future.”

The controversy stems from claims that the Jama Masjid mosque, constructed during the Mughal period, was built after demolishing a pre-existing Hindu temple dedicated to Lord Harihar. Such disputes echo larger historical narratives surrounding the construction of religious sites during India’s Mughal era.

On 19th November, a court-mandated survey was conducted at Jama Masjid in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh. The court ordered the survey in response to a petition filed by Supreme Court Advocate Vishnu Shankar Jain, and seven co-plaintiffs, asserting that the mosque occupies the site of a temple dedicated to Bhagwan Kalki.

Destructuring the petition:

In the petition, it has been asserted that the Jama Masjid in Sambhal was constructed on the centuries-old Shri Hari Har Temple, dedicated to Bhagwan Kalki and destroyed by Babar. The petitioners added that the site holds significant religious importance for Hindus and was forcibly and unlawfully converted into a mosque during the Mughal period. The petitioners further argued that it is a centrally protected monument as per the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904 and is listed as a monument of national importance by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Some key points from the petition:

-ASI has not done anything to maintain the property and members of the Muslim community have taken advantage and captured the entire property.

-Some people have formed a Committee known as Intezamia Shahi Jama Masjid Committee and are not NOT allowing any person in public to access the property. Vishnu Jain himself was not allowed to freely enter in August.

-Mosque side is preventing even ASI to control it

– Mosque side has locked a portion of the property without any right to do so.

They further contended that, being devotees of Bhagwan Vishnu and Bhagwan Shiv, they have the right to access the temple for worship and homage. They asserted that the right to worship has been denied by the mosque’s management committee. Furthermore, they also accused the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) of failing to fulfil its statutory duty to ensure public access to the site. They cited Section 18 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, while seeking access to the site.

The petitioners emphasised that the current situation infringes upon their constitutional right to practise their religion and called for immediate action to restore public access to the site.

Backed up Evidences:

Furthermore, the petition mentioned that during the reign of Akbar, the Ain-i-Akbari was written, which also referred to a prominent temple in Sambhal named Hari Mandir. The text described the temple as being dedicated to Bhagwan Vishnu and the prophesied birthplace of Bhagwan Kalki’s avatar. It further highlighted that the temple held importance during Akbar’s time, suggesting that Hindus had temporarily reclaimed the site before subsequent Mughal interventions.

Ain-i-Akbari read, “There is game in plenty in the Sarkar of Sambel (Sambhal), where the rhinoceros is found.! It is an animal like a small elephant, without a trunk, and having a horn on its snout with which it attacks animals. From its skin, shields are made and from the horn, finger-guards for bow-strings and the like. In the city of Sambal is a temple called Hari Mandal (the temple of Vishnu) belonging to a Brahman, from among whose descendants the tenth avatar will appear in this spot. Hansi is an ancient, the resting-place of Jamal the successor of Shaikh Farid-i-Shakar ganj.“

According to the petition, several archaeological surveys were conducted in Sambhal during 1874–76 by Major-General A. Cunningham, who was the Director General of the ASI. He wrote a report titled “Tours in the Central Doab and Gorakhpur”, which mentioned the architectural elements of the temple that survived the conversion.

Some parts of the book on Sambhal read, “The principal building in Sambhal is the Jami Masjid, which the Hindus claim to have been originally the temple of Hari Mandir. It consists of a central domed room upwards to 20 feet square, with two wings of unequal length, that to the north being 500 feet 6 inches, while the southern wing is only 38 feet 1 1⁄2 inches. Each wing has three arched openings in front, which are all of different widths, varying from 7 feet to 8 feet.”

24 November, 24

Violence erupted in Sambhal after a court-ordered survey at Jama Masjid, as Islamists gathered and started pelting stones at the police. They resorted to arson and clashed with the police present at the scene. The police had to resort to tear gas and baton charge to control the Islamist mob. Several vehicles were set ablaze in the area, and stone pelting continued for hours.

The survey was carried out under the supervision of Advocate Commission. A heavy police force was deployed in the area to ensure the survey proceeded peacefully.

The developments started at around 6:30 AM when a team, including the District Magistrate and Superintendent of Police, arrived at the mosque to conduct the survey. A mob of around 2,000 Muslims gathered outside the mosque and demanded the survey to be stopped.

When the police tried to intervene, the mob started pelting stones, which forced the authorities to retreat briefly. Sources at the site of the incident said that SDM and PRO of SP Sambhal were among the injured as Islamists allegedly attacked the police. Several vehicles belonging to Sambhal police were set ablaze by the Islamist mob. Furthermore, the sources said that Islamists from nearby areas also reached Jama Masjid and joined the mob.

During the survey, however, Muslims living in the area gathered outside the Jama Masjid and raised religious slogans. The District Magistrate of Sambhal confirmed that the survey was completed in around two hours and stated that a report would be submitted to the Civil Court, which will review it on the next date of hearing, 29th November 2024.

Meanwhile, All India Muslim Jamaat Chief Shahbuddin Razvi Barelvi appealed to the minority community in Sambhal to maintain peace and tranquillity, and not to indulge in vandalism and stop stone pelting.