Agrasen Ki Baoli

Agrasen Ki Baoli: An Ancient Reservoir with a Mysterious Past

Tucked away amidst the modern skyline of New Delhi, Agrasen Ki Baoli is a stunning yet enigmatic stepwell that echoes the architectural grandeur of a bygone era. This ancient structure, located on Hailey Road near Connaught Place, is a historical marvel that has sparked numerous speculations about its origins. While officially attributed to Maharaja Agrasen, a legendary king from the Mahabharata era, the present structure is believed to have been rebuilt during the 14th or 15th century by the Agrawal community. However, certain architectural elements hint at an even older, possibly Hindu temple influence, raising the question: Could Agrasen Ki Baoli have been a sacred Hindu site before evolving into a functional stepwell?

Architectural Brilliance of Agrasen Ki Baoli

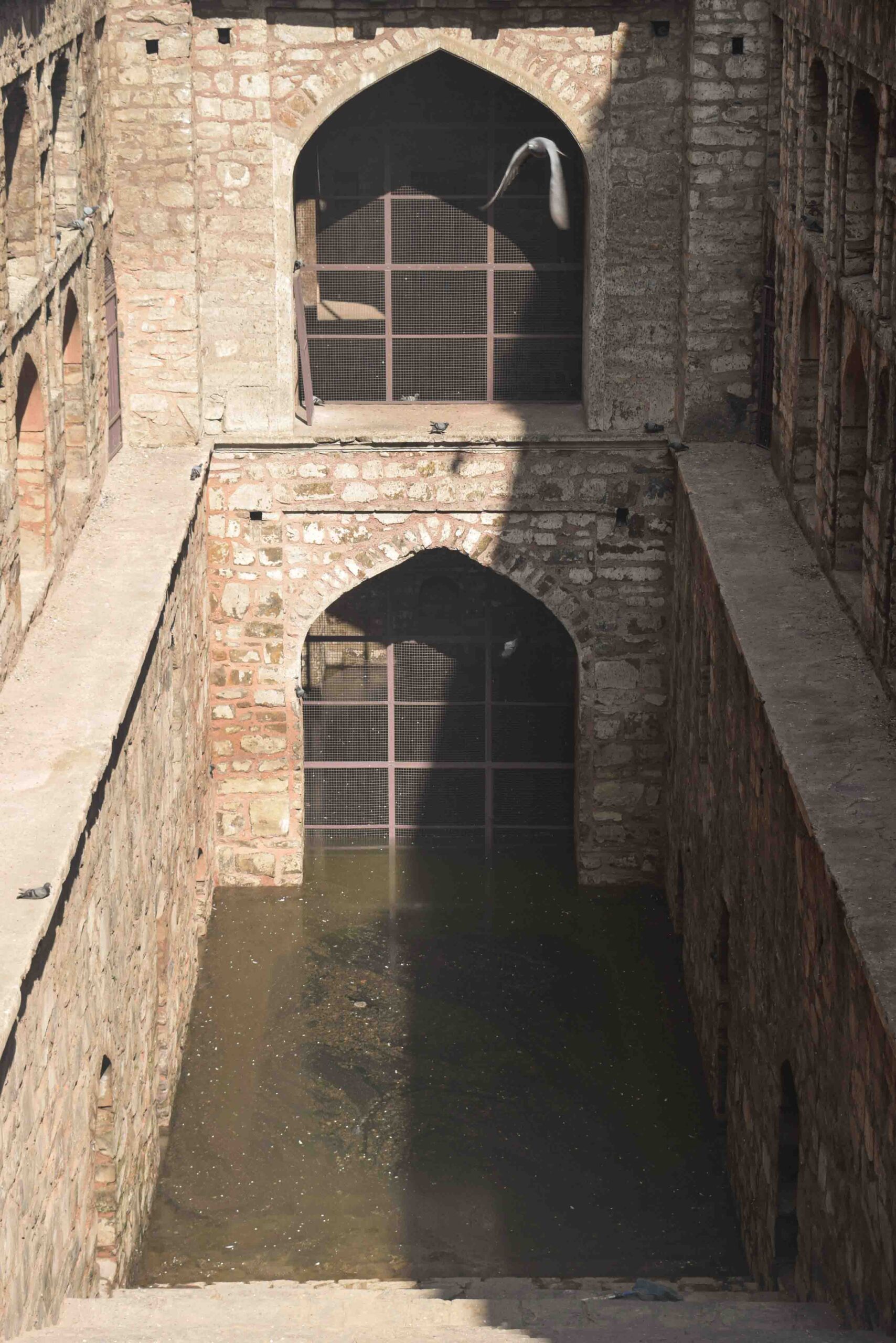

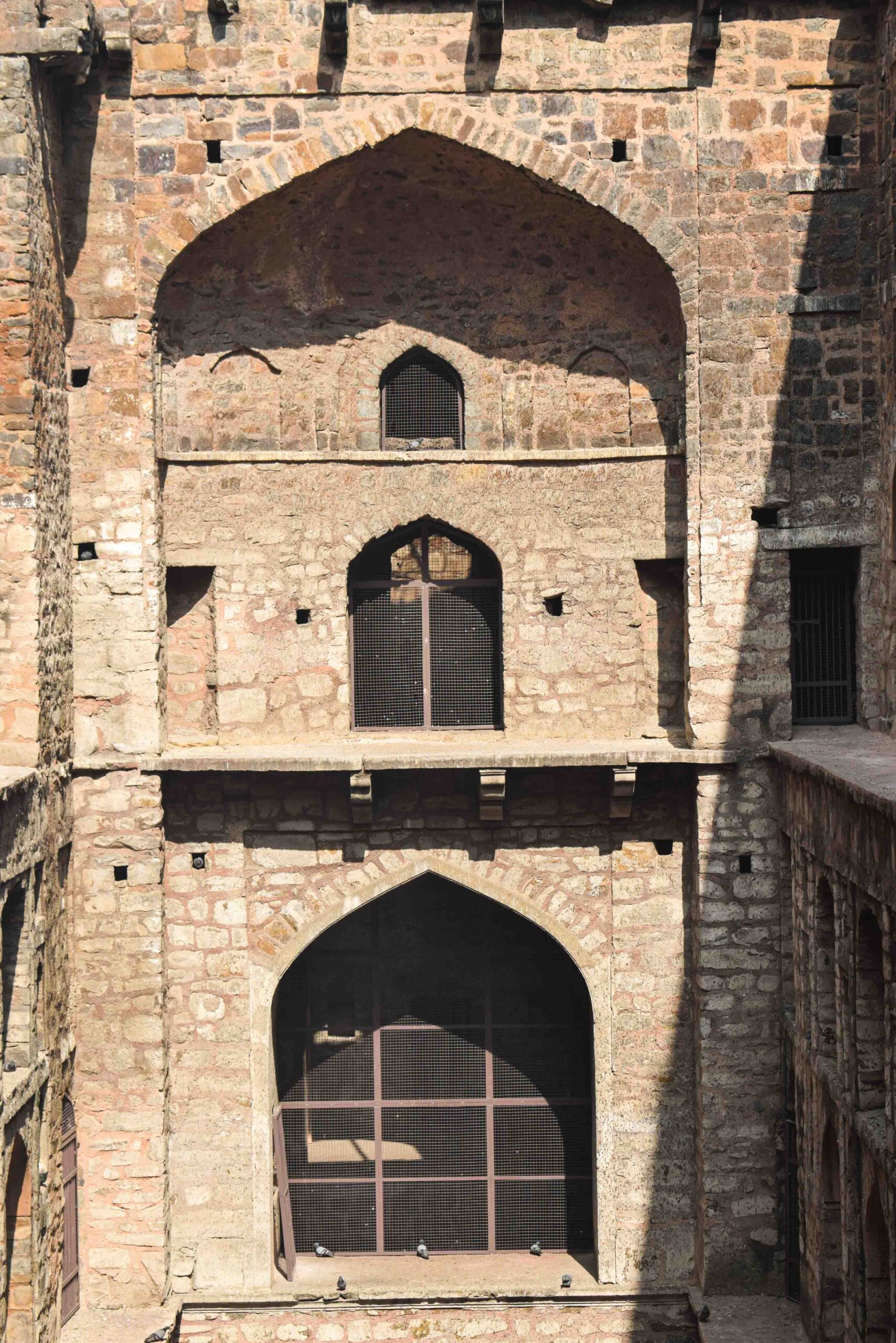

Agrasen Ki Baoli is an architectural gem, featuring 103 stone steps that lead down to the now-dried reservoir. The rectangular structure measures approximately 60 meters in length and 15 meters in width, exhibiting a sophisticated multi-tiered design with arched niches and chambers on either side. The structure is composed of three levels of arched corridors, providing an eerie yet captivating visual experience as one descends towards its depths.

Key Architectural Features:

- Stepped Reservoir: The main feature of the baoli is its series of descending steps, allowing access to the water source regardless of seasonal changes in water levels.

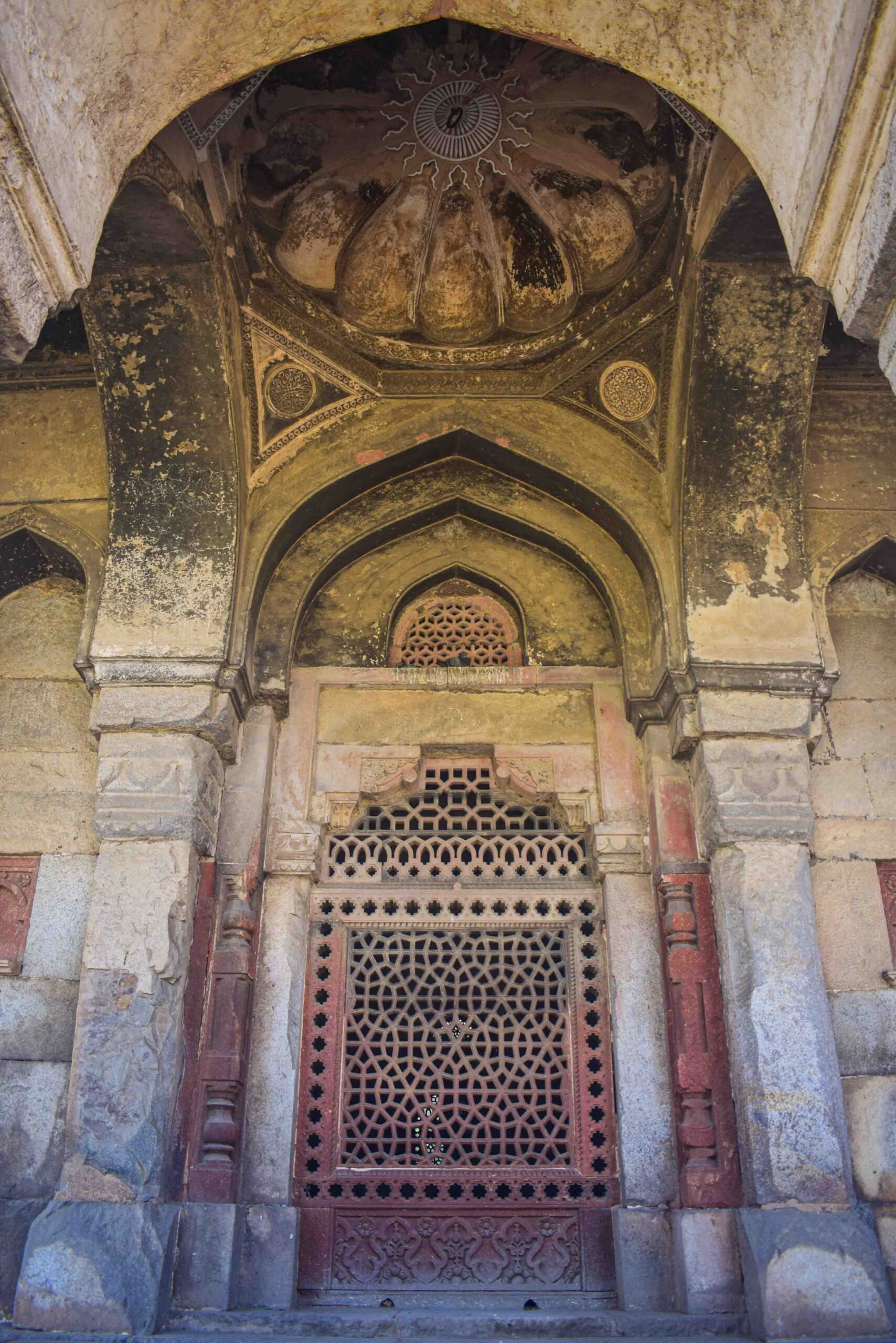

- Ornate Pillars and Niches: The walls of the baoli are adorned with intricately carved niches and alcoves, some of which bear resemblance to Hindu temple mandapas (pillared halls) commonly found in ancient temples.

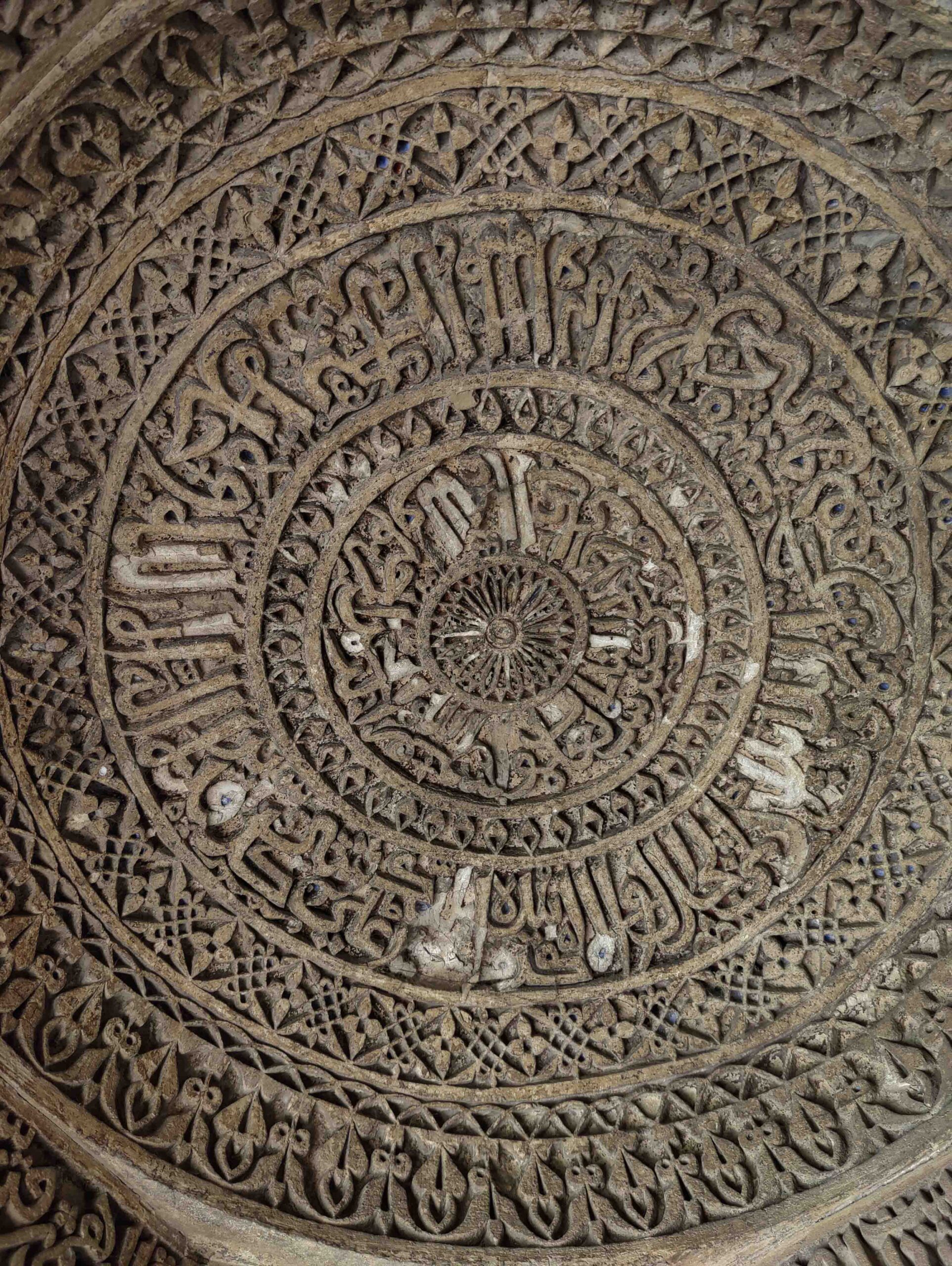

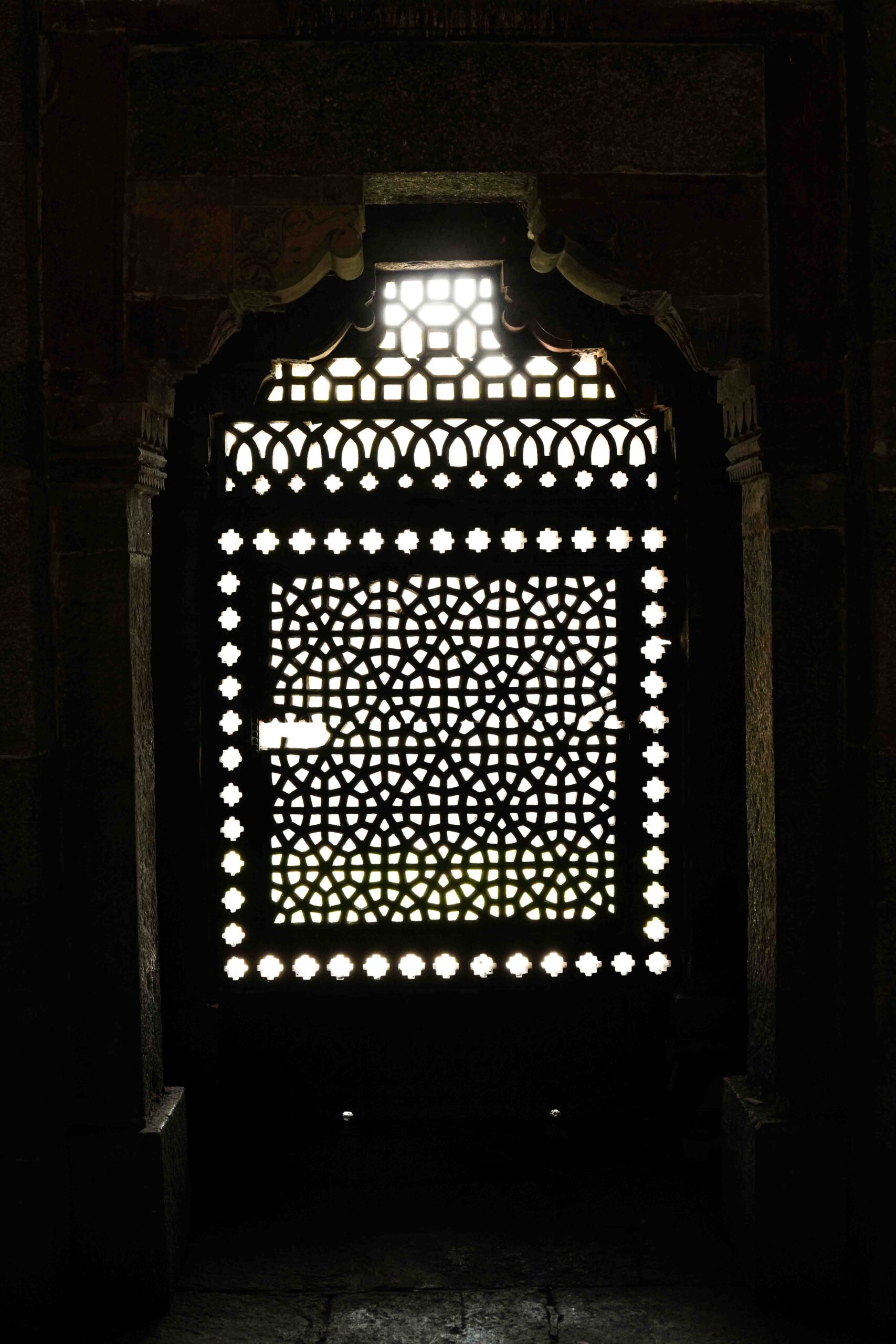

- Floral and Geometric Motifs: The carvings on the baoli’s walls showcase lotus patterns and floral engravings, both significant symbols in Hinduism.

- Arched Chambers: While the pointed arches on the walls are reminiscent of Indo-Islamic influences from the later periods, the presence of certain semi-circular arch designs aligns more closely with Hindu and Jain architectural traditions.

- Presence of a Shrine: Some historical accounts and local lore suggest that a small shrine or temple once existed within the baoli premises, potentially indicating its earlier use as a religious site before being converted into a utilitarian structure.

Hindu Temple Influences in Agrasen Ki Baoli

Despite being labeled a medieval stepwell, certain elements suggest the baoli may have had religious significance in the pre-Islamic era:

- Symmetry and Vastu Alignment: Traditional Hindu water structures, like temple tanks and stepwells, were built in strict accordance with Vastu Shastra, ensuring harmony with the natural elements. Agrasen Ki Baoli’s geometric precision and alignment with cardinal directions strongly indicate adherence to these ancient architectural principles.

- Sculptural Relics: While many of the original carvings have been eroded over time, faint traces of Hindu deities or auspicious symbols have been reported in historical studies.

- Connection to Sacred Water Bodies: Water has always played a crucial role in Hindu religious practices, and stepwells were often attached to temples or pilgrimage sites to facilitate ritualistic bathing and water conservation. Agrasen Ki Baoli’s grand scale and careful construction suggest it may have served a similar purpose before being repurposed.

- Legends of King Agrasen: The baoli’s association with Maharaja Agrasen, a ruler linked to Sanatan Dharma and Vedic traditions, strengthens the theory that this site originally had religious significance.

Possible origins of the Ancient Site

Several factors contribute to the hypothesis that Agrasen Ki Baoli may have been a sacred Hindu site before being repurposed:

- Cultural Transition Over Centuries: Delhi has witnessed multiple dynastic transitions, from Hindu rulers to Turkic and Mughal invaders. Many Hindu structures were modified, repurposed, or overlaid with newer architectural elements.

- Islamic conversions of Hindu Stepwells: Several stepwells across North India, originally built by Hindu kings, were later used or renovated by invaded rulers. The addition of Islamic-style arches at Agrasen Ki Baoli suggests later modifications rather than an original feature.

- Absence of Inscriptions: Unlike most Mughal-era constructions, which prominently feature Persian calligraphy, Agrasen Ki Baoli lacks any clear inscriptions attributing it to a specific ancient ruler, reinforcing the possibility that its origins predate Islamic rule in Delhi.

Conclusion

The key factor of this article is to understand the origins of the Ancient monument and to understand if any possible conversions of the site is discovered.

Agrasen Ki Baoli stands as an architectural enigma, seamlessly blending elements of Hindu, Jain, and later Islamic styles. While its functional role as a stepwell is undisputed, the presence of Hindu architectural motifs, its alignment with Vastu principles, and the legends surrounding its origins all fuel speculation that it was once a sacred Hindu site. Whether it was a temple tank, a spiritual retreat, or simply a grand water reservoir, its past remains shrouded in mystery. More archaeological and historical research may yet unveil the deeper secrets of this Ancient Baoli.